Take a Book With You

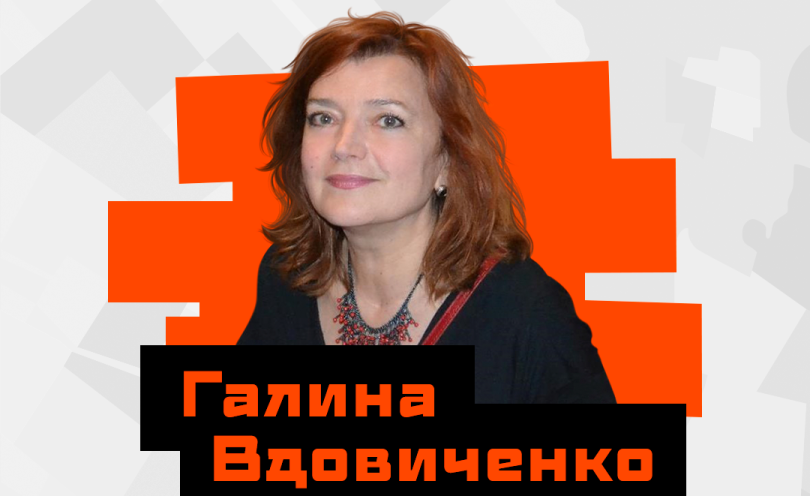

It’s August 2022, and we’re in Peremoha village, located in the Zolochiv district north of Kharkiv. The adults are waiting in line for a bus that will bring humanitarian aid while the children sit with us on a blanket spread out on the grass. We’ve set aside the books we brought and have begun crafting butterflies from beads. As we follow the instructions of Halyna, a volunteer from Kharkiv, we’re all engrossed in the task, trying to tame the stubborn needles. It feels almost like a collective meditation session.

We refrain from discussing the topic of war, as it’s evident from the ominous rumbles in the sky. „It’s ours!“ exclaim the children, quickly returning to their butterfly-making. Within a few moments, another plane streaks across the sky, leaving fiery flashes on either side. Someone loudly calls out „Home!“ while searching for the children, but most remain transfixed, watching the plane with intense gazes.

„That second plane is not one of ours,“ a woman with a baby in her arms says as she approaches us. The plane has already flown past, so there’s no reason to be frightened. „There’s one with such a horrible sound it makes kids urinate themselves out of fear. It’s like a roar from hell.“ She then asks if we have any books to spare. Despite the gravity of the situation, the woman’s smile is childlike, revealing two missing front teeth.

„I have seven children,“ she nods, indicating where her children are within the circle. „Three are mine, and four belong to my friend. Unfortunately, we only have one book since we are not at home. We’re originally from Luhansk region, but we came here before everything started, and there was nowhere else to go. My husband is fighting, and we were fortunate that he wasn’t home when the occupiers entered our village. One woman led them around the village and pointed out where fighters from the Anti-Terrorist Operation were hiding… Eventually, they were all rounded up and shot near the church.“

A preschool-aged girl cradles a baby in her arms, and her gaze belies her young age. The children quietly listen to the woman’s story, studying the visitors carefully. Despite our best efforts, we feel like we are merely passing through, leaving behind a sense of indebtedness. Kharkiv volunteers and a handful of Ukrainian PEN authors continue to press on, but every encounter with the communities of Derhachi and Zolochiv districts leaves our hearts aching.

„What’s the name of your village?“ I ask the children at our next stop.

„It doesn’t have a name; it’s just a village,“ one of the children replies.

We hope to leave some books at the village or school library, as we did in Podvirky and Peremoha. While essential supplies such as groceries are undoubtedly helpful, there’s also a growing need for books, as many people have asked us to bring some along.

However, a young girl, who appears to be around eight or nine years old, interjects: „I can’t read.“ Another child of a similar age nods in agreement, „Me neither.“

„How can that be? It can’t be true!“ I think to myself. But then it dawns on me: these children have spent one-third of their lives living in extraordinary circumstances, with two years of a pandemic followed by war. Children in frontline villages haven’t had the opportunity to develop a love for reading.

In today’s Ukraine, books are destroyed by shelling or at the hands of the occupiers. The liberated towns are often left with a grim, apocalyptic scene of devastated libraries. Those who can do so collect and send books to places where they are desperately needed, as they are now considered essential items. However, the demand for books always seems to exceed the supply.

There is also a growing thirst for Ukrainian books abroad, as many Ukrainian children live as refugees. Some activists and institutions have been trying to stock foreign libraries with Ukrainian books, but the demand far exceeds the available supply.

I was overjoyed when I saw the news and a photo of a shelf stocked with Ukrainian books at the Oodi library in Helsinki. The next day, a friend from Finland wrote to inform me that the books had already been checked out by the library’s avid readers, disappearing like water poured onto parched earth.

„Where can we buy Ukrainian books?“ attendees at the Latvian Children’s Book Festival in Riga ask me after my reading.

At the Frankfurt Book Fair, I overhear a conversation between two women: „I thought you could buy them, but no, you can only flip through them.“

„Well, what did you expect? It’s an exhibition,“ the other woman responds.

During the Batumi/Odesa International Literary Festival in Georgia, I hear from some mothers after meeting with children: „There are only Russian books in bookstores.“ The women even went so far as to list books they wanted to order from those I had brought with me.

On the same day, I stumbled upon a large bookstore on the corner of two central streets in Batumi, boasting an impressive selection of books. However, to my dismay, there were no books available in Ukrainian. The shelves were stocked with books in Russian, including one titled Tales About Young Heroes, featuring a girl from the Young Pioneers on the cover. This brought back memories of my Soviet childhood when such books were often given to us to supplement our home libraries. Want to read Pippi Longstocking? It’ll go along with Young Heroes. The illustrations are even the same, as if taken from a past life.

Despite the passage of so many years, Moscow continues to terrorize the minds of young readers with propagandistic fiction, spreading its moldy spores not only in its domestic market but also in foreign territories within its reach.

Despite the ongoing war, new bookstores open in my incredible country, and libraries serve as volunteer centers. During a visit to a bookstore in Lviv, a girl said, „My books are back home in Kharkiv. Mom said to bring only one book and one toy with me.“

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve heard that phrase from refugees about a book being one of the essential items in their backpack…

While weaving camouflage nets at the library on Rynok Square, I met many children, including Yurchyk from Brovary, Agnieszka from Kharkiv, Tarasyk from Lviv, and Levchyk from Irpin…

„We need a butterfly right here,“ someone suggests, and the children’s hands quickly knot a short ribbon.

When I first heard about our plans to create butterflies at the Kharkiv volunteer center near the camouflage net, I didn’t initially think about beadwork. The war has transformed the meaning of so many words, and now when I hear the word „butterfly,“ I picture wings on a camouflage net. And with the thought of a new book for children, an idea takes shape.

Translated by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan